As I dug deeper, however, I started finding documents that were much older; from the early history of the school in the 1900s to artifacts from the 1950s when the school was built in its current location. There were photographs from inside the school as well as photographs of students and staff.

While fascinating to look through, I initially did not see a use for these artifacts other than occasionally sharing entertaining “throwbacks” with staff via email. The boxes stayed in the closet while I found my footing as a new library teacher and attempted to map out my curriculum for each grade level. My primary focus was to connect what we learned in library with what students were learning in the classroom.

One such connection was with fifth grade, who completes a unit each year on founding documents. To prepare students for this work in their classroom, I spent multiple library lessons on all things related to primary sources. In years past I would teach these lessons using famous examples of primary resources from history such as pages from Anne Frank’s diary or the photograph of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg. More recently as I was preparing to deliver these primary source lessons to a new set of fifth graders, I opened that library closet once again and saw the boxes filled with the school’s history. This time something clicked. Why not use these resources in my teaching? I decided I would use the photographs and documents to teach the primary source unit.

After spending a class reviewing with students what a primary source is, I provided students with photocopies of the photograph down below and, without any context, I asked them to write down their observations. As students studied the photograph I could see the realization begin to form and a number of hands began to raise with students asking “Ms. Riordan, is this OUR school?” The excitement was palpable in the library after I confirmed that the photograph was in fact of our school auditorium. The students scrutinized the photograph with their classmates at their tables and furiously wrote down their observations and pointed out details in the photograph. After ten minutes, I called students back to the rug and put the photograph under the document camera.

As educators, it can be a struggle to impart to our students the “why” of what they are learning. Why should students care about this? This lesson reinforced for me the importance of making students feel connected to their learning. When students feel invested, engagement increases and that is when students can reach a new level of understanding.

I realize that not every lesson lends itself to this kind of connection and not everyone has access to these types of artifacts in their schools but incorporating local history into my teaching has been a great way to engage students and make their learning even more meaningful.

After completing the primary source unit with fifth grade and seeing how successful it was, I began looking for other ways to incorporate local history into my teaching. During my master’s program at Simmons, I heard time and again from my professors that forging community partnerships was an important piece of librarianship but I was unsure of what that looked like in an elementary school library.

Fortunately, I had recently attended a professional development involving the local historical society and thought they would be a great community connection. In the winter of 2020, I reached out to see if there was a way we could collaborate. As luck would have it the historical society was in the process of developing a program centered around local immigrants in the 1900s and their stories. The historical society was looking to pilot the program with a local school.

The focus of this work was perfect for my fourth grade students who complete a unit on immigration each year that typically involves working on a project around their own family’s immigration story as well as learning about well known topics such as Ellis Island.

To prepare for this program I met with the historical society and the fourth grade teachers to plan our approach. We determined that I would lay the groundwork with students around primary and secondary sources in library class. That work would then be reinforced in the classrooms, through their family immigration project, and then members of the historical society would come to the school and present to fourth grade students about Newton’s history of immigration.

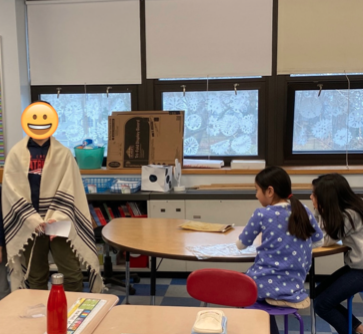

When the historical society came to our school in late February 2020, students were put in groups and given the name of a real immigrant to Newton in the 1900s. In addition, students were provided with primary sources and artifacts such as clothing, jewelry and tools belonging to that immigrant provided by the historical society. Students were excited to handle real artifacts and learn about people who once lived in the very same neighborhoods as they do.

The majority of cities and towns in Massachusetts have their own historical society that preserves and maintains local history. This is a great place to start if you are looking to make connections with the community as these organizations are often eager to form relationships with schools as well. Incorporating local history into my lessons required minimal effort on my part and yet produced highly rewarding experiences for students and is something I will continue to weave into my teaching going forward.