|

Liza Halley is the Library Teacher at Plympton Elementary School in Waltham, MA

I want to focus on the convergence of comics and social justice, and for the majority of this article, I will be stepping outside the typical classroom. I am interested in how reading graphic novels on a particular topic can help shape our ideas about society and justice. How does bringing comics to particular spaces, like refugee camps and prisons, create a more just world? How can comics give voice to those often overlooked and underrepresented?

0 Comments

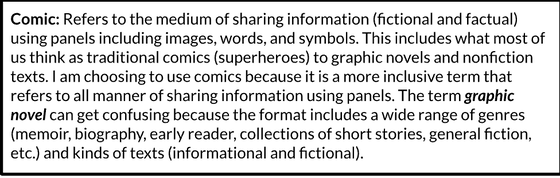

Liza Halley is the Library Teacher at Plympton Elementary School in Waltham, MA I want to start off discussing some language I use when talking about the medium of comics. People often ask me: What’s the difference between a graphic novel and a comic? Here’s a simple boilerplate to explain: Comics is a good catch-all term to use, graphic novels often just refers to a bunch of comics bound together.

Gillian Bartoo is the District Cataloger for Cambridge Public Schools in Cambridge, MA Let’s talk about classifying graphic books. Usually when somebody says to me that their graphics cataloging is a mess what they usually mean is the classifications, or call numbers, are a mess: some are classed as 741.5, some as FIC, and some with other Dewey numbers. Raina Telgemeier’s Smile is in FIC or 741.5 (“work of imagination, comic book”) but Sisters is at 306.8 (“family relationships”). Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales are in FIC, 741.5 and 973. El Deafo is cataloged as a biography. Maus I is at 741.5, because it is assigned as a classic text of comic book study, but Maus II is at 940.53 (“World War II”). Every Batman has a different cutter. Manga has an extended 741.5952 call number. Early reader graphics are split between Early Reader and Graphic collections and have both E and 741.5 call numbers. How does anyone get this stuff to sit together in a logical way?

|

Forum NewsletterCo-Editors

|