I start my introduction with a video that is primarily book covers, dozens of titles that, according to the ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom annual field reports, have been challenged or banned over the years. I go broad with the examples to help illustrate the wide variety of titles people challenge and to give students a lot of ideas for their own selection. The video serves as an activator, leaving students with the question of whether challenges are ever justified or if the freedom to read should be without limits.

We use the ALA’s definitions of banned and challenged materials to ensure we are all working with the same understanding. I then share the history of banning books in the United States, going back to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which is considered to be the first widely-banned book in the U.S. We discuss how a combination of regulations and shifting societal norms led to censorship, and the eventual establishment of Banned Books Week in 1982. From there we look at who initiates challenges and the popular reasons titles are challenged. Students can easily make the connection that most often adults trying to protect children are responsible for challenges and bans.

Asking that they keep this information in mind, we then assign students a position either in favor or against banning an example title, And Tango Makes Three. Reading aloud to 8th graders is, of course, one of the highlights of the unit for me, and it always reminds me of the power of teaching with picture books at any grade level. Using evidence from the text, students make arguments for and against banning the book, most making the connection that the book normalizes LGBTQ+ families. While the majority of our students would unquestioningly support queer families, they are asked to form a counter argument in their paper, and this a prime example of how the same point can be utilized by different sides.

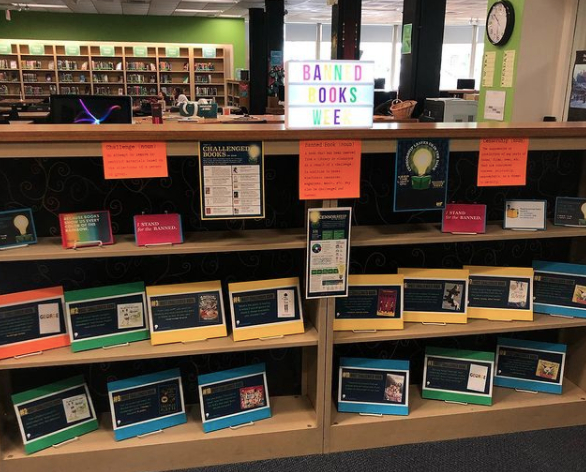

Students select a banned or challenged title to read independently, and their teacher then guides them through the opinion writing process. Realizing the value of writing for an audience, we publish the students’ final papers on the library website. Admittedly, I’m often surprised by the conservative stance some students take on profanity or sexual content, but I am always encouraged by their arguments to use literature as a window to the world. Teachers can choose any number of topics to teach opinion writing through, but by partnering and making a connection between the library world and their writing, the experience is more meaningful and has a lasting impact on the students as readers.