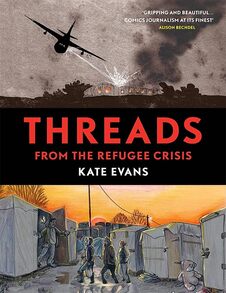

“...If you read a comic about a real person, doing real things, showing actual examples of honesty, integrity, vulnerability, and generosity . . . That explodes the myth of the other, the migrant, the invading horde, the dangerous terrorist, or the African savage. [It explodes] all those racist tropes that are used to keep people out because they are from poorer countries. I hope that that can . . . literally break down borders.”

Evans wrote Threads after volunteering at a refugee camp in Calais, France for ten days. Over the course of her three trips to the camp, she does this kind of myth exploding. This is a book that introduces us to real people fleeing war, hoping for a safe and stable future in Europe. Since Threads’s publication in 2017, many powerful graphic memoirs have been published by and about refugees, including The Best We Could Do (Bui), When Stars Are Scattered (Mohammed & Jamieson), Alpha Abidjan to Paris (Bessora), Manuelito (Amado), and Year of the Rabbit (Veasna). These books play an important role in breaking down stereotypes regarding refugees and bringing the reader into the refugee experience intimately, helping large audiences visualize the experience of destabilization due to unstable governments, war, and violence.

Comics can also be used as a tool for empowering people who experience crisis, trauma, and war. Ali Fitzgerald spent ten years teaching comics to refugees in Berlin, Germany, and collected her experiences in Drawn to Berlin: Comic Workshops in Refugee Shelters and other Stories From a New Europe. She used these workshops to connect with people, to make a space for them to feel heard and seen, and to help refugees process some of their trauma through images and words. Fitzgerald’s book chronicles her time teaching comic workshops, highlighting the lives of some of her class participants.

Refugees are also creators themselves. In 2019, Amnesty International continued a program to collaborate with artists to combine self expression and storytelling with education, even when hardly any paper or books are available. The comics they support and create service the communities in which they are born; a few examples include a comic set in SirLanka about LBGTQI rights, Guantanamo Kid: The True Story of Mohammed El-Gharani, and an info-comic written about the Energy Transitions plank of their Climate Change campaign.

Comics such as these are examples of activism. Creating comics to advocate for undervalued and underrepresented groups raises awareness and, sometimes, money. In Pakistan, Imran Azhar of AZ Corp Entertainment decided to create a comic books series that offers positive role models to youth and address issues youth in Pakistan face. AZ Corp first releases the comics in Young Offenders Industrial School, a juvenile detention center, before being offered to the public. Azhar describes AZ Corps comics this way: “Team Muhafiz is about diversity; Mein Hero is about self-realization, critical-thinking and local action; and Basila is about social taboos, citizen activism and journalism. Our comic books are all about harmony and diversity. Although we are targeting children, teenagers and the youth, our indirect beneficiaries are adults.” Azhar has created a corporation with a mission to promote civics, social justice and gender equity themes through comics, video, and audio production.

Another social justice comic creator is the UK-based Positive Negatives. Positive Negative produces comics, animations, and podcasts about contemporary social and humanitarian issues, including conflict, racism, migration and asylum. They accomplish this by combining ethnographic research with illustration, the adaptation of personal stories into art, and education and advocacy materials. Their materials are used worldwide, and even in higher education institutions like Brown University’s Choices Program, which uses Syrian Refugees, Understanding Stories with Comics.

Prisons have also been a place where activists bring graphic art to empower incarcerated individuals to gain art and literacy skills as well as to give a voice to their lives and experiences. In Colorado, a Denver nonprofit called Pop Culture Classroom teaches inmates art and literacy through comic workshops and Brink Literacy Project created the Frames Prison Program to increase literacy rates and reduce recidivism. Through Brink’s graphic memoir course, they work with individuals to develop their storytelling skills, promote literacy, spark critical thinking, and help them grow through self-reflection. States like California and Wisconsin also have arts programs in their prisons that also include comic workshops (California Arts in Corrections, Wisconsin Prison Humanities Project).

So, as a classroom teacher, why is it important to know about work in refugee camps and prisons? No matter what grade you teach, we are all trying to educate citizens of the world. Many of us have curricula that touch on world topics, even in the younger grades, that address social justice themes: challenges children face in the world, human rights, environmental equity, and access to education. As librarians, one of the strands in the AASL standards across grade levels is to share knowledge in an interconnected world. Comics can be a vehicle to meet these standards— both creating them and reading them, especially those created by and for people living in circumstances outside our school communities.

In terms of library lessons, we could all give library lessons based on Imran Azhar’s work with children in Pakistan. Azhar did some crowdsourcing in three schools in Pakistan: Lyari, Shireen Jinnah Colony, and SOS village. He asked the children to follow “just three rules: the hero they created must embody the characteristics of their locality; it had to be a boy and a girl, and that they could not defend violence with violence.” AZ Corp Entertainment created new superhero comics based on Azhar’s work in that community. Across grade levels, we could, using those three guidelines, ask students to create a superhero character and then to write their own comics that they could share with their friends and family or even circulate in the library.

If you’re looking toward collection development of your graphic novel section, the following books lists will help you find graphic novels that address social justice issues:

- Social Justice Books: Teaching for Change Project

- ALA Graphic Novels & Comics Round Table Social Justice and Comics Reading List

- Great Schools: Racism, Climate Change, and Social Justice

Comics and social justice are here to stay and there will be more of them in the future. What are your thoughts on this topic? Have you heard of other programs that use comics as a form of advocacy? Have you heard of people teaching comics in alternative settings? Reach out or keep the conversation going in the comments below.

Brown, P. (2017, April 8). No license plates here: Using ART to TRANSCEND prison walls. The New York Times. https://www.rutlandherald.com/no-license-plates-here-using-art-to-transcend-prison-walls/article_ed4352e2-3ea0-5159-b284-c6cf60cfce67.html

Price, D. (2018, March 23). Laziness does not exist. Medium. https://humanparts.medium.com/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01

n.a. (2023). About the Program. California Arts in Corrections. https://artsincorrections.org/about

https://wisconsinprisonhumanitiesproject.wordpress.com/syllabus-comics-workshop-spring-2019/

https://theconversation.com/refugee-comics-personal-stories-of-forced-migration-illustrated-in-a-powerful-new-way-106832

https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1251646/download