Little did my new friend know, he was sitting next to a librarian who has made it her special mission to disabuse teachers, parents, administration, and students of this very notion: sequential stories - graphic novels, comics, graphic nonfiction - are really books that you read, and your brain is doing a ton of work while you read them. They are for all readers.

. . .We communicate graphically, through icons and imagery much more than we realize. And I think, for the most part, we are communicated to graphically (emphasis added). . . . And because it’s not primarily text, and we don’t have a grammar and understanding of it, we’ve never learned to talk about images and icons. . . . So it becomes one-way communication: We’re being talked at but we can’t talk back. We can talk back verbally but that’s in a different language and it pushes different buttons. That’s part of what draws me to this and the other things I do: I want to learn the language that is being spoken to me.”

You might be wondering, where should I start? In this article, I want to offer you some specific lessons that can be used with the whole range - K-12 students, as well as recommend a few articles to read, to get you moving forward on your journey to incorporating graphic novels into your future lesson planning. I am choosing to focus on lessons that help students and teachers to become better readers of graphic novels, and become more mindful of what they are doing when they read in the medium of graphic works.

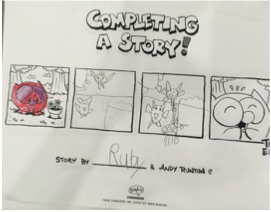

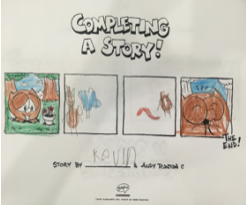

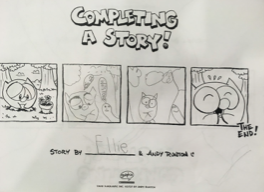

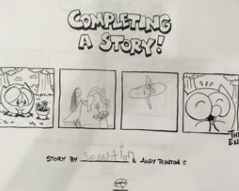

I usually break my lessons down to five general categories: panels, gutters, expression, sound and time. I won’t be able to show examples of lessons in all of these categories in this article; I will focus on teaching readers about panels and expressions. For lessons, I pull from already existing comics online (easy to project images). I love Andy Runton’s site (creator of Owly), which offers several free complete short stories to use as examples (and downloadable pdfs). I also love to use MacMillan Publishers excerpt from Maris Wick’s Human Body Theater. Depending on the author and publisher, you can often find excerpts of graphic novels to use as examples on their websites. I like to start off with seeing what students know about comics and the way graphic novels tell stories. After that, I help students build a language around what a panel is, how to read panels (which direction to move the eye), and then we delve into a whole host of questions to consider. Here is an example of some questions you might pose to a class:

- How do the panels work together?

- How does the author use panels on this page?

- How does the panel affect your sense of time in the story?

- Can you explain what is happening in the gutter between three panels on this page?

- Which panel on this page most helps to move the plot of the story along?

- Which panel on this page helps you to understand more about the main character in this story?

- Which panels show the conflict around which this story focuses?

- Now that you have read the entire story, can you find any panels that foreshadow what will eventually happen?

- How does the shape of the panel contribute to the meaning of the story or moment in the story?

- How do symbols help you understand how a character is feeling or what she or she is doing?

One other example of a lesson I love to teach centers around the way dialogue works in a graphic novel and how important it is to read the expressions on characters’ faces. Take a page from a graphic novel and mute out all the words, then ask students to write what they think the characters are saying to each other. Here is an example of a few panels from a page from Ben Hatke’s Might Jack. The lesson allows students to talk about the role of facial expressions, body language, and dialogue in story telling and in reading graphic novels. It also makes the reader much more aware of what they are doing when they read a graphic novel. This lesson can also be used as a way to introduce SEL topics, especially with students who have trouble reading facial expressions and body language and talking about feelings.

If this article sparks your interest, I would suggest you read the following three articles to learn more about how you can either teach graphic novels in your library classroom or encourage teachers to think about graphic novels in new ways.

Mike Cook and Jeffrey S.J. Kirchoff. Teaching Multimodal Literacy Through Reading and Writing Graphic Novels

Stephen Cary. Going Graphic: Comics at Work in the Multilingual Classroom

Jed Olebaum. An Interview with Toon Book Founder Francoise Mouly.

Please do not hesitate to reach out to me at [email protected] if you would like to keep the conversation going.

Row, D. K., “Interview with David Byrne.” Portland Oregonian, March 2, 2005.