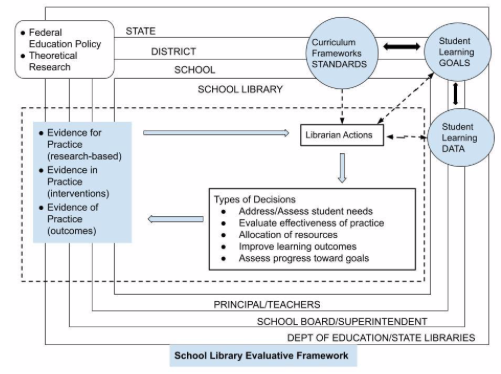

My analysis of over 30 state impact research studies published between 1993 and 2018 to explores how the impact of the school library and librarian on student achievement has changed and presents a revised conceptual framework called “Evaluation of School Libraries” (Figure 1). It illustrates the position of the school library within the context of the school, district, and state.

Figure 1

A Short History of Library Studies

Keith Curry Lance led a number of impact studies in the 1990s and 2000s: beginning with Colorado I and II (1993), then followed by Alaska (2000), Pennsylvania (2000), New Mexico (2002), Iowa (2002), and Michigan (2003). Other impact studies led by others followed in Massachusetts (2000), Texas (2001), Florida (2003), North Carolina, (2003); many use his methodology and survey instrument. State standardized test scores in reading are used as the measure of student learning for these studies, reflecting the national trend in which measuring student achievement within school districts was shifting toward standardized test scores. "The staffing of the library with a full time, certified librarian correlates strongly with higher standardized test scores, rather than any one specific program, such as classroom collaborations, instruction, and reading promotion (Baumbach, 2003; Baughman, 2000; Burgin et al., 2003; Lance et al., 2000a; Lance et al. 2000b; Lance et al., 2002; Rodney et al., 2002; Rodney et al., 2003; Smith, 2001).

After 2003 a more nuanced analysis emerged in a number of studies in which librarian activities are described and analyzed in more detail and depth. The American Association of School Libraries (AASL) published The Role of the School Library Media Specialist in Site-Based Management in 2003 and then Standards for the 21st Century Learner in 2008. The revised descriptions of learning in the school library and role of the librarian provide a means to integrate descriptions of learning and skills specifically resulting from instruction in the library. This means that the librarian has a curriculum they deliver, related to concepts such as inquiry research, using technological tools, synthesizing information, or following the information search process. Although many studies continue to measure student learning using standardized state reading scores, several more qualitative studies cite or develop survey questions from these new AASL standards in order to assess student learning more holistically (Baumbach, 2003; Governor’s Task Force, 2005; Gordon & Cicchetti, 2018; Klinger et al., 2009; Lance & Schwartz, 2012; Todd, 2012; Todd & Kuhlthau, 2005b; Todd & Kuhlthau, 2000c).

The 2008 Standards for the 21st Century Learner connects access to a school library to the issue of equity in education, building on the earlier studies that demonstrated that there is less access to libraries in high poverty districts. All students, particularly those classified as disadvantaged, should have access to a high-performing school library that provides a unique learning opportunity that promotes critical thinking through inquiry-based research, information literacy, and information seeking. Although many earlier Lance, or Lance-inspired, studies (Alaska, 2000; Florida, 2003; Michigan, 2003; New Mexico, 2002; North Carolina, 2003) addressed equity by comparing reading scores and access to a school library in the top performing and lowest performing schools, the question of equity drives the entire Massachusetts study (Gordon & Cicchetti, 2018) with a focus on socio-economic demographics.

Later studies describe libraries as places of active learning and use qualitative methods to interrogate the impact on student learning (Baumbach, 2003; Klinger et al., 2009; Lance & Schwartz, 2012; Rodney et al, 2003; Small et al., 2010; Smith, 2006; Todd, 20012; Todd & Kuhlthau, 2005b & 2005c). Evidence is used to better evaluate, sustain, and strengthen the role of the school library. The are key takeaways on which librarians and administrators are the following points of leverage.

Points of Leverage

Libraries are Places of Active Learning

Critical thinking, information literacy, literacy, self-reflection, synthesis of information, and knowledge creation are key components of student learning during knowledge formation and the information search process. Todd & Kuthlthau (2005) describe the school library as an “agent” of active learning in their Ohio study (p. 85), underpinned by theories such as Kuhlthau’s information search process during research and Todd’s knowledge formation. Todd (2015) explains that “evidence of practice focuses on the real results of what school librarians do” (p. 10) yet evidence of student learning outcomes are not being produced. As an example of this, Todd (2012) says that in the New Jersey study “few librarians could cite specific learning outcomes in relation to the students’ development of deep knowledge and deep understanding of content area and… had difficulty focusing on student outcomes” (p. 22). He notes that outcomes are assumed when a school librarian provides instruction or an instructional intervention. This theme emerges in many state impact studies that describe interventions by librarians such as meeting with students, teaching information literacy, providing reading incentive programs but without evidence from these direct interventions reported. Learning outcomes continue to be measured outside of the library through classroom or standardized testing scores (Baughman, 2000; Burgin et al., 2003; Lance et al., 2000; Lance et al., 2002; Lance et al., 2005; Rodney et al., 2003; Small et al., 2010; Smith, 2001; Smith, 2006). A more complex and nuanced analysis of active learning in the school library, specific activities of librarians, and clear goals set by the librarian and principal together. Increasing opportunities in educator graduate programs and professional development about the role of the school library and its impact on learning outcomes could shift the perception teachers and principals have of the role of the school librarian.

Building Capacity for Collaboration

The collaborative role of the librarian with the teacher is one of the most important points of leverage but can vary based on the perception of the teacher and administrator. In many studies, the lack of a common vision about the role of the library and librarian can be a barrier to working together (Lance & Schwartz, 2012, p. 1). In addition, Todd (2012) explains “dimensions of information literacy focus on knowledge construction, and are generally considered [by teachers] to be in the domain of classroom teachers” (p. 12). This problem is rooted in the norms popularized by educational institutions, systems, and state agencies. The responsibility to ensure a high-quality school library program requires that librarians, teachers, school and district leaders, and state education agencies have a clear, agreed-upon role of the librarian.

Such agreements include a plan for fiscal support of library programs, expectations for professional collaborations, and a clear view of goals for professional development. Roberson et al. (2005) suggest pre-professional programs for all educators integrate strategies for collaborating with school libraries and that there is “a dire need…to begin to develop and align curricula in professional education programs to ensure instruction on the role and value of school libraries and the inclusion of strategies that allow for greater collaboration between all members of the school’s educational team” (p. 51). Through collaboration, student learning outcomes are formulated, curriculum and instruction is developed, and evidence can be collected demonstrating to what extent the learning goals were met.

Role of the Principal

Perceptions can shift when school leadership has a clear vision and expectations of the role of school librarian as collaborator and instructional leader. The role of the principal as instructional leader emerges as a central theme in the 2000s. Specifically, a number of impact studies emphasize the importance of a collaborative relationship between principal and school librarian to better define the role of the librarian (Lance et al., 2000b; Siminitus, 2002; Smith, 2001; Rodney et al., 2002; Rodney et al., 2003; Lance et al., 2002). Baumbach (2003) goes the furthest by suggesting there be required training for school and district leadership to learn how to support, create, and evaluate a high-quality library program. The Mississippi studies (Roberson et al. 2003 & 2005) were early to articulate this problem and provide solutions, starting with the premise that “[The principal’s] attitude and support of the school library program is one of the greatest determining factors of whether or not a school’s library will have the attributes necessary to positively influence academic achievement” (Roberson et al., 2003, p. 99). The problem is that despite the many studies and evidence of school libraries impact on student learning, this information has not reached principals consistently. In their study on principal, teacher, and librarian perceptions, Roberson et al. (2005) found that “the data suggests that school professionals develop their attitudes towards librarians within the school setting…professional education programs [should] ensure instruction on the role and value of school libraries and the inclusion of strategies that allow for greater collaboration between all members of the school's educational team” (p. 51).

The Florida study (Baumbach, 2003) recommendations are more specific, and build on Florida’s existing information systems, programs, and policies. The study specifically describes types of professional degrees and emphasizes the need for outreach to colleges to ensure future librarians are in the pipeline. In addition, Baumbach (2003) recommends addressing equity and budget issues by following state and national standards for school libraries, widely disseminating state, national, or district information literacy standards; creating professional development opportunities for all stakeholders, and coordinating library data collection (pp. 94-100). The points of leverage for improving school libraries in Florida are both centralized with state education leaders and localized within districts.

State Agencies

Although evidence-based practice and the role of the principal are key areas of exploration(Governor’s Task Force, 2005; Governor’s Task Force, 2006; Lance et al., 2010; Lance & Schwartz, 2012; Roberson et al., 2005; Small et al., 2010; Smith, 2006; Todd, 2012; Todd & Kuhlthau, 2005b; Todd & Kuhlthau, 2005c), other studies broaden the responsibilities for a successful library to state education agencies and higher education institutions (Governor’s Task Force, 2005; Governor’s Task Force, 2006; Klinger, 2009; Lance et al., 2010; Lance & Schwartz, 2012; Small et al., 2010; Smith, 2006; Todd, 2012). The state education departments hold an essential role whether as a study sponsor, provider of data, or providing library curriculum frameworks (Baumbach, 2003; Burgin et al., 2003; Governor’s Task Force 2006; Lance et al., 2000; Lance & Schwartz, 2012; Smith, 2001; Todd, 2012). Continued research is needed to explore the relationship between administrator training, evaluation, and the barriers to the growth of school libraries as places where student learning outcomes are measured and documented. Additionally, more research is needed to explore the extent to which learning standards related to library instruction, like information literacy, inquiry research, and reading programs, are integrated into school curriculum and instruction.

Assessing the Impact

All states that conducted impact studies over the last 25 years have had increases in the number of state-certified full-time librarians except Alaska, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas. However, the percentage of libraries and state-certified librarians in each of these states remains high, between 89% and 95% except Alaska. The states with the highest percentage of libraries and certified state librarians are Florida (91% of schools have libraries; 93.4% of librarians are state certified) and Pennsylvania (95% of schools have libraries; 93.7% of librarians are state certified). Alaska and Massachusetts have the fewest school libraries at 75% and 77%, respectively.

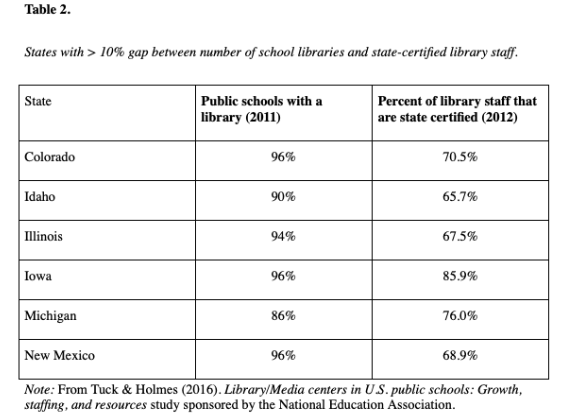

Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, and New Mexico have a gap of more than 10% between schools with a library and library staff that are state certified (see Table 2).

Of course, there are limitations. School libraries and state certified librarians are almost ten years old. In addition, it is not known to what extent the data is accurate since it relies on each state’s unique data collection system and department of education that may or may not collect data on school libraries.

Conclusion

Achieving equitable access to a school library for all students is a complex undertaking that requires advocacy from within and outside the school library. Smith (2006) explains in the Wisconsin study that administrators need to support concrete goals of collaboration between librarians and teachers because otherwise the librarian is left to seek out reluctant teachers. This “cheerleading” takes time away from instructional and program work and can lead to burnout (p. 4). School libraries rely on leadership to advocate for the space,set expectations,secure adequate funding, and assess progress toward goals.

An aspirational model is to ensure that librarians and teachers gain experience through practice and professional development to set goals, develop instructional units, and evaluate outcomes at the school, district, and state levels. Doing so would create a convergence in the school library of the entities that surround and influence learning. There is still research to be done to examine to what extent educator evaluation regulations and professional development makes a difference in curriculum and instruction at the school, district, and state levels. At the school, district, and state levels education departments drive educational outcomes and can improve learning outcomes through evidence-based practice that includes collaborative planning, instruction, and assessment of progress toward goals.

Achterman, D.L. (2008). Haves, halves, and have-nots: School libraries and student achievement in California [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas]. UNT Digital Library. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc9800/

Baughman, J. C. (2000, October 26). School libraries and MCAS scores [Paper presentation]. Symposium, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, Simmons College, Boston, MA, United States.

Baumbach, D. J. (2003). Making the grade: The status of school library media centers in the Sunshine State and how they contribute to student achievement. Hi Willow Research & Publishing.

Burgin, R., Bracy, P. B., & Brown, K. (2003). An essential connection: How quality school library media programs improve student achievement in North Carolina. RB Software & Consulting.

Everhart, N., & Logan, D. K. (2005). Research into practice: Building the effective school library media center using the student learning through Ohio school libraries research study. Knowledge Quest, 34(2), 51-54.

Falkenberg, N., Gould, D., Davis, M., & Sheldon, S. (2017, January). Report on the Baltimore library project: Years 1-3. Weinberg Foundation.

Francis, B. H., Lance, K. C., & Lietzau, Z. (2010, November). School librarians continue to help students achieve standards: The third Colorado study. Library Research Service.

Fusarelli, L.D., & Fusarelli, B.C. (2015). Federal education policy from Reagan to Obama: Convergence, divergence, and 'control'. In L.D. Fusarelli, J.G. Cibulka, & B.S. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of education politics and policy (pp. 189-210). Routledge.

Gordon, C. A., & Cicchetti, R. (2018, March). The Massachusetts school library study: Equity and access for students in the Commonwealth.

Governor's Task Force on School Libraries State of Delaware. (2005, February). Report of the Delaware school library survey (R. J. Todd, Author). Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries, Rutgers, State University of NJ.

Governor's Task Force on School Libraries State of Delaware. (2006, April). Report of phase two of Delaware school library survey: "Student learning through Delaware school libraries" (R. J. Todd & J. Heinstrom, Authors). Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries, Rutgers, State University of NJ.

Gretes, F. (2013, August). School library impact studies: A review of findings and guide to sources. Weinberg Foundation.

Kachel, D. E. (2013). School library research summarized: A graduate class project. Mansfield University.

Klinger, D.A., Lee, E.A., Stephenson, G., Deluca, C., & Luu, K. (2009). Exemplary school libraries in Ontario: A study by Queen's University and people for education. Ontario Library Association.

Lance, K. C. (1994). The impact of school library media centers on academic achievement. SLMQ, 22(3).

Lance, K. C., Hamilton-Pennell, C., & Rodney, M. J. (2000a). Information empowered: The school librarian as an agent of academic achievement in Alaska schools. Revised edition. Alaska State Library.

Lance, K. C., & Loertscher, D. V. (2005). Powering achievement: School library media programs make a difference: The evidence mounts (3rd ed.). Hi Willow Research & Publishing.

Lance, K. C., Rodney, M., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2002, June). How school libraries improve outcomes for children: The New Mexico study.

Lance, K. C., Rodney, M. J., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2000b). Measuring up to standards: The impact of school library programs & information literacy in Pennsylvania schools. Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education.

Lance, K. C., Rodney, M. J., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2000c). How school librarians help kids achieve standards: The second Colorado study.

Lance, K. C., Rodney, M. J., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2005). Powerful libraries make powerful learners: The Illinois study. Illinois School Media Association.

Lance, K. C., Rodney, M. J., & Schwartz, B. (2010). The Idaho school library impact study-2009: How Idaho librarians, teachers, and administrators collaborate for student success (Research Brief Spring 2010). Idaho Commission for Libraries.

Lance, K. C., & Schwartz, B. (2012, October). How Pennsylvania school libraries pay off: Investments in student achievement and academic standards. RSL Research Group.

Lance, K. C., Welborn, L., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (1993). The impact of school library media centers on academic achievement [in Colorado]. Hi Willow Research & Publishing.

Loertscher, D. (2000). Taxonomies of the School Library Media Program. Hi Willow Research & Publishing.

Maurer, J. (2020). State of school libraries in Oregon: Challenges and Successes. OLA Quarterly, 26(2), 19-25.

The Ontario Library Association. (2006). School libraries & student achievement in Ontario.

Roberson, T., Schweinle, W., & Applin, M. B. (2003). Survey of the influence of Mississippi school library programs on academic achievement: Implications for administrator preparation programs. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 22(1), 97-113. https://doi.org/10.1300/J103v22n01_07

Roberson, T. J., Applin, M. B., & Schweinle, W. (2005). School libraries' impact upon student achievement and school professionals' attitudes that influence use of library programs. Research for Educational Reform, 10(1), 45-51.

Rodney, M. J., Lance, K. C., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2002). Make the connection: Quality school library media programs impact academic achievement in Iowa. Iowa Area Education Agencies.

Rodney, M. J., Lance, K. C., & Hamilton-Pennell, C. (2003). The impact of Michigan school librarians on academic achievement: Kids who have libraries succeed. Library of Michigan.

Selwyn, N. (2014). Data entry: Towards the critical study of digital data and education. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(1), 64-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.921628

Siminitus, J. (2002). California school library media centers and student achievement: A survey of issues and network applications. SBC Pacific Bell.

Small, R. V., Shanahan, K. A., & Stasak, M. (2010). The impact of New York's school libraries on student achievement and motivation: Phase III. School Library Research, 13, 1-27.

Smith, E. G. (2001, April). Texas school libraries: Standards, resources, services, and students' performance. Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Smith, E. G. (2006, January). Student learning through Wisconsin school library media centers: Case study report. EGS Research & Consulting.

Sorensen, R. J. (1994). Survey of school library media programs in Wisconsin: A brief report of statistics. Bureau for Instructional Media & Technology.

Tepe, A. E., & Geitgey, G. A., Student. (2005). Student learning through Ohio school libraries, introduction: Partner-leaders in action. School Libraries Worldwide, 11(1), 55-62.

Todd, R. J. (2012). School libraries and the development of intellectual agency: Evidence from New Jersey. School Library Research, 15, 1-29.

Todd, R.J. (2015). Evidence-based practice and school libraries: Interconnections of evidence, advocacy, and actions. Knowledge Quest, 43(3), pp. 9-15.

Todd, R. J., & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2005a). Listen to the voices. Knowledge Quest, 33(4), 8-13.

Todd, R. J., & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2005b). Student learning through Ohio school libraries, part 1: How effective school libraries help students. School Libraries Worldwide, 11(1), 63-88.

Todd, R. J., & Kuhlthau, C. C. (2005c). Student learning through Ohio school libraries, part 2: Faculty perceptions of effective school libraries. School Libraries Worldwide, 11(1), 89-110.

Tuck, K. D., Ph.D., & Holmes, D. R., Ph.D. (2016). Library/Media centers in U.S. public schools: Growth, staffing, and resources. National Education Association.